MËMORY—MONUMEИTS

Ιmperial nostalgia, colonial aphasia, postcolonial melancholy are some of the terms that have been used to describe the distancing of the brutal history of colonialism and slavery from contemporary European public memory — and responsibility. Today, around the world, grassroots demands for a critical history of the present are challenging power by radicalizing remembrance as part of an agenda of restitution, reparation and repair.

This thematic cluster, centered on narratives and materialities, starts from the assumption that the linear chronologies of national history, its institutions, such as the archive, university and museum, its symbolic organization of public space and exhibitionary architectures, as well as its gendered division of agency – heroes vs. mothers, are themselves central artifacts and technologies of European colonialism. Black, indigenous and anti-colonial thinkers have long pointed out the impossibility of dismantling the edifice of western colonial power, patriarchy and white supremacy with the “tools of the master.” What is at stake then is not so much the addition of stories of the marginalized to the official archives, as a break with the logics that excluded them to start with (or included them in problematic ways).

Today as the bicentennial celebration of the Greek Revolution begins to unfold as a European success story, the moment seems ripe to bring these urgent demands for the decolonization of knowledge, of the university and the museum in dialogue with critical discussions, research and initiatives through which academics, artists, architects, museologists and activists in Greece have already been contesting the Greek monumental landscape — broadly understood as the manifestation and projection of dominant historical narratives and actors in the public sphere in statuary, monuments, rituals and institutions of knowledge.

The marble statue of the Diadoumenos (“diadem-bearer”) held by two workers from Mykonos, during the first French archaeological excavations on Delos (1894). Courtesy of the French School of Athens. Source: Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades

Narratives

The dominance of the nation-state as a frame for narrating history has made it difficult to trace linkages and processes across states, continents and oceans, related to colonial histories – as well as to resistances to them. Furthermore, the habitual narration of the history of Europe from within its geographical borders as an anthology of national histories, enables the convenient “offloading” of the bloodiest crimes of colonialism back to the histories of former colonial possessions, fostering a sense of white innocence and white superiority. Meanwhile as historians of the Subaltern Studies Collective have discovered in their struggles to write truly emancipated, decolonized histories, the conventions of academic history discourse in and of themselves enshrine the “Europe” – of modernity, capitalist progress, citizenship and the nation-state – as secret subject of all national histories.

The emplotment of Greek history as a chapter of European history thus inevitably produces silences, which derive from a bedrock of white supremacist ideology. Reading Greek history from former colonies rather than the metropole suggests some possible questions to explore:

- Why does the intellectual and material connection of Greek rebels to other revolutionaries outside Europe, such as the Haitian ones, who defeated their French masters and abolished slavery forever in 1804, appear as a footnote in Greek national histories? Rather than interpret the Greek Revolution as a derivative of the European Enlightenment, assumed to be the mainspring of emancipation, could we use the “unthinkable” Greece-Haiti link to flip the script and open a potential path toward provincializing Europe and decolonizing Hellas?

- How has incorporation into the “family of white nations” obscured possible avenues of comparative research — and collective activism — around histories of debt or restitution of artefacts from European museums that might place Greece in the same frame with Haiti or Benin?

- Might the linear history of the Greek nation “from antiquity to the present” be juxtaposed to that of other modern nation-states scripted within the mold of European prototypes, such as India, which also has been imagined as the rebirth of an ancient civilization and similarly views its Muslim past as a barbarous “dark age,” justifying contemporary discrimination against Muslim minorities?

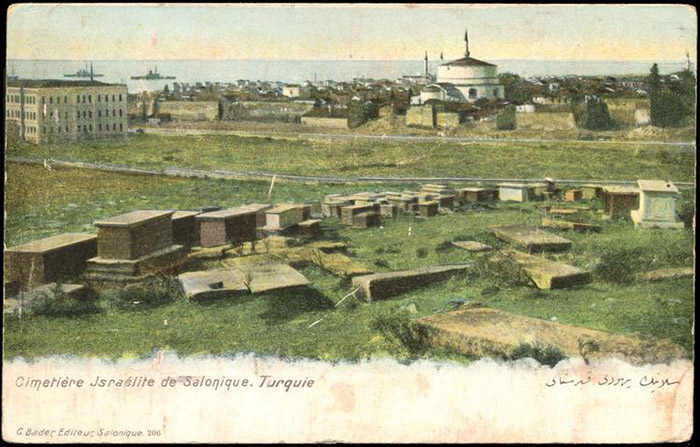

Postcard of the Jewish Cemetery of Thessaloniki by German watchmaker G. Bader. 1915. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Materialities

It is unquestionable that the (re)viewing of the monumental landscape in Greece is of key significance for the decolonization of Europe. At the same time this process plays a central role in ongoing local struggles against racism, xenophobia, patriarchy and islamophobia. Τhe questions that follow are based on a search for new methodologies for both understanding and activating memory beyond institutionalized ideas of the historical that routinely separate the past from the present, imagination from truth and the bodies and the senses from objects and environments.

- An abundance of studies by historians, archaeologists, curators and anthropologists have examined how the colonial genealogies of “Hellas” have been made material in contemporary Greece through its use as an outpost to manifest the European origin story by way of a capillary networks of excavations and museums. Less explored has been the impact of this massive exhumation of ancient bodies as an embodied, enacted and disputed practice — and form of labor — on modern Greek identification with whiteness. How has the ambivalent inclusion of modern Greeks in the sphere of white Europeanness blocked comparison with practices of necroviolence, including stripping corpses of their objects and museum display, targeting black and brown “natives” and their lands in the context of settler colonialism?

- The establishment of the Greek state entailed the destruction and/ or lack of care for the artefacts of populations that do not fit into the purified ethno-religious national culture or suit the classist ideals of its elite, including religious/political buildings, folk architecture, personal items, non-Orthodox cemeteries. For many years now, research and public interventions by academics, architects and artists have documented and restored these marginalized materialities in Greek space, demonstrating their significance for the restitution of the history of those populations and their contemporary presence in Greek society. Could we read in these combined practices of conservation of ancient materialities and destruction or neglect of others modes of identification with European ideas of whiteness — and, conversely, in histories of non-compliance to racialized hierarchies potential openings toward cosmopolitical associations and alternative cosmologies?

- In many places around the world, the racialized, patriarchal and heteronormative ideals inscribed in the monumental landscape are being contested through spectacular acts of physical defacement, as well as community discussions, counter-tours and architectural contests. How might these global developments be brought into productive dialogue with analogous critiques and political performances of redress in the Greek context, particularly those that have been staged in the past by anti-nationalist, anti-militarist, feminist and queer groups?

- What could it mean to “decolonize the museum” or “decolonize the university” in the Greek context?

convener: Penelope Papailias

The toppled statue of the 33rd U.S. President Harry S. Truman during demonstrations in Athens. 2006. Credit: Eurokinissi